Canada Gazette, Part I, Volume 157, Number 21: Regulations Amending the Valuation for Duty Regulations

May 27, 2023

Statutory authority

Customs Act

Sponsoring agency

Canada Border Services Agency

REGULATORY IMPACT ANALYSIS STATEMENT

(This statement is not part of the Regulations.)

Executive summary

Issues: The existing legislative and regulatory framework governing the methods of determining the value for duty (VFD) of imported goods creates an unfair advantage for non-resident importers (NRIs), which are businesses located outside of Canada that ship goods to customers in Canada. This advantage exists due to NRIs’ ability to declare a lower VFD on goods they import to Canada by using an earlier sale price and not the sale to an actual buyer located in Canada that brought the goods into Canada. The earlier sale price that is used in these instances occurs in the earlier stages of the supply chain,footnote 1 including a sale transaction between a foreign-based manufacturer and an NRI.

The ability to declare a lower VFD means that these NRIs pay less customs duty on the goods they import into Canada when compared to Canadian importers, i.e. importers residing in Canada. Since Canadian importers are paying higher amounts of duties, the existing framework puts Canadian businesses at a competitive disadvantage, while simultaneously resulting in lost customs revenues to Canada in duties paid on lower VFD.

Description: The proposed regulatory amendments would clarify which sale is to be used to calculate the duty on imported goods in order to address a regulatory gap that unduly benefits businesses located outside of Canada (NRIs) that ship goods to customers in Canada by (i) defining the term “sold for export to Canada”; and (ii) amending the definition of the term “purchaser in Canada”.

Clearly defining these terms would ensure that the VFD of imported goods is based on the “sale” that caused the goods to be imported to Canada and will ensure that the term “sale” is given a broad meaning that includes purchase commitments or purchase orders, as well as intents to purchase, arrangements, and any other type of understanding that causes goods to be imported to Canada.

Rationale: The existing legislative and regulatory framework requires renewal to ensure alignment with international obligations, to reflect modernized business practices in order to protect Canadian importers’ ability to compete on a level playing field with NRIs, to provide greater certainty and predictability for the importing community, and to give the CBSA the authority to enforce the collection of the correct amount of revenue from import duties owed to the Government of Canada.

A preliminary consultation was launched in July 2021, providing all stakeholders, including industry stakeholders, the opportunity to ask questions or provide comments on the proposed amendments. The feedback received was analyzed and taken into consideration in the development of these proposed amendments.

Issues

The global importing community has changed substantially in the recent decade, reflecting new business models and other innovations in the marketplace, most notably in e-commerce, where Canadian consumers no longer need to enter a brick-and-mortar commercial establishment and businesses are able to purchase and receive products from foreign vendors without having to coordinate the transaction through manual processes. Over the last decade, there has been a growing share of imports involving non-resident importers (NRIs) with minimal operations and investments in Canada, as well as increasingly complex cross-border sales transactions that involve companies owned, controlled by, or in partnership with foreign entities shipping goods directly to Canada from third countries. E-commerce volumes have increased dramatically as the result of the impact of COVID-19 pandemic-related restrictions on purchases from domestic brick-and-mortar establishments and this shift is not anticipated to decrease, which will only exacerbate this issue.

The Customs Act and the corresponding Valuation for Duty Regulations (the Regulations) that govern the methods of determining the value for duty (VFD) of imported goods in Canada do not currently align with international consensus established at the World Customs Organization regarding the interpretation of the term “sale”, and the “last sale rule”. Specifically, the term sale is to be interpreted in its widest sense, and the last sale to the buyer in the country of import, and not an earlier sale between two foreign entities, is to be used as the basis for determining the VFD. Canada’s narrow interpretation of the term sale, which focuses on when the transfer of title occurred, as well as a loophole in the definition of “purchaser in Canada” that was highlighted by recent decisions from the Canadian International Trade Tribunal (CITT), permit the use of a sale between two foreign entities as the basis for calculation of the VFD.

This misalignment creates an unfair advantage for NRIs as they can use the earlier sale between two foreign entities in the trade chain. For example, the sale between the foreign-based manufacturer and the NRI, which occurs so that the NRI can fulfill the order to the buyer located in Canada, is used in order to pay less duty on goods that are imported to Canada.

To address these issues, the Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA) proposes amendments to the Regulations to provide clearer direction to importers when determining which sale is to be used for assessing the value of their imports, with the intention of establishing a level playing field among all importers, while simultaneously reducing lost customs revenues to the Government of Canada in duties paid on lower VFD.

Background

A VFD must be declared for all goods imported to Canada. The VFD is the base figure on which duty owed on imported goods is calculated. Even if no duty is owed, the VFD of goods must still be established so that any applicable assessment of the goods and services tax, provincial sales tax or harmonized sales tax may be calculated.

The CBSA administers Canada’s valuation program for imported goods in accordance with the valuation for duty provisions outlined in the Customs Act and the Regulations. Together they establish the basis for the valuation of imported goods, and implement Canada’s international obligations pursuant to the World Trade Organization’s Agreement on Implementation of Article VII of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade 1994,footnote 2 which is also referred to as the Customs Valuation Agreement. The Customs Valuation Agreement establishes a fair, uniform and neutral system for valuing goods in accordance with commercial reality, and prohibits the use of arbitrary or fictitious customs values. Its goal is to ensure that the customs value of all goods entering all World Trade Organization member countries is established using the same rules, and that the valuation of goods is not a barrier to trade. Canada and most of its trading partners value imported goods based on the rules included in the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement.

The Customs Act outlines six methods, to be applied in hierarchical order, through which the VFD of imported goods must be established:

- Transaction Value Method — VFD is based upon the price paid or payable for the goods, which is generally shown on the invoice, with adjustments for certain elements.

- Transaction Value of Identical Goods — VFD is based upon the transaction value (that is, a value determined under the first method) of identical goods that were imported at about the same time, trade level and quantity.

- Transaction Value of Similar Goods — Essentially the same as the transaction value of identical goods, except that the basis of VFD is the transaction value of similar goods.

- Deductive Value — VFD is based on the domestic selling price of the goods (or identical or similar goods) in Canada, less an amount that represents either the commission paid or the profit earned and general expenses incurred on a unit basis in selling the goods in Canada, as well as deductions for certain other elements.

- Computed Value — VFD is based on the cost of production of the goods, plus amounts that represent the profit earned and general expenses incurred on sales for export to Canada as well as additions for certain other elements.

- Residual Method — If all previous methods have been examined and found to be inapplicable, under this method, the VFD will be derived from a flexible application of one of the previous methods of valuation set out in Customs Act (e.g. published price lists).

The primary method is the Transaction Value Method and it must be used whenever possible to determine the VFD of imported goods. A key obligation in the Customs Valuation Agreement is for World Trade Organization members to rely on the Transaction Value Method as the primary basis of determining the VFD. This ensures a fair and predictable environment for the trading community, consistent with the objectives of free and liberalized trade. The subsequent five valuation methods are more complex and are only to be used if the criteria for the Transaction Value Method are not met.

The Customs Act identifies three requirements that must be met to apply the Transaction Value Method. These requirements are as follows:

- (a) The imported goods were sold for export to Canada;

- (b) The purchaser in the sale for export is the purchaser in Canada; and

- (c) The price paid or payable for the goods can be determined.

In short, the Transaction Value Method applies where goods are “sold for export to Canada to a purchaser in Canada.” The price of that sale is the basis for the calculation of customs duties and taxes.

Currently, the term “sold for export to Canada” is not defined in the Customs Act. In 1997, the Valuation for Duty Regulations amendments came into force (SOR/97-443, Canada Gazette, Part II, Vol. 131, No. 20), giving effect to a definition of “purchaser in Canada” in the Customs Act. The intent was to prevent the undervaluation of imports by preventing the importer from using a sale between two foreign entities to value the goods, rather than the sale to a person in Canada.

While there is no definition of “sale” in the Customs Valuation Agreement, international consensus among World Trade Organization members was established at the World Customs Organization that the term “sale” is to be interpreted in its widest sense,footnote 3 meaning the sale does not need to be concluded prior to the importation of the goods (i.e. not be restricted to a sales contract, but also include agreements to sell, which could be in a form of purchase commitments, purchase orders, intents to purchase or any other agreement that causes goods to be imported to Canada). More importantly, it was also agreed that the last sale to the buyer in the country of import, and not an earlier sale between two foreign entities, is to be used as a basis for determining the VFD (“last sale rule”).footnote 4

In the absence of a definition for the term “sold for export to Canada” in the Act, in 2001, a Supreme Court of Canada decisionfootnote 5 established that, for the purpose of applying the Transaction Value Method of determining the VFD under the Customs Act, the sale for export to Canada is the sale by which title to the goods passes to the importer. The CITT subsequently relied on the Supreme Court of Canada’s narrow interpretation of “sold for export to Canada”, which puts emphasis on the transfer of title, in making its decisionsfootnote 6 resulting in the last sale rule not always prevailing. In addition, another CITT decisionfootnote 7 highlighted a loophole in the definition of the term “purchaser in Canada” in the Regulations by allowing the transaction between a foreign seller and an NRI that is not importing the goods on speculation, specifically when an agreement to sell exists with a permanent establishment in Canada, to be the transaction to establish the value for duty. Such a transaction is, in fact, a foreign sale. These decisions have effectively allowed NRIs to structure their transactions in order to benefit from paying lower duties on imported goods, due to the fact that the valuation is not determined on the basis of the actual last sale.

These cases brought to the CITT have established case law, highlighting the misalignment between Canadian law and international consensus regarding the interpretation of the term “sale” and application of the “last sale rule”.

Compliance

The CBSA relies primarily on voluntary compliance for the assessment of duties and conducts post-importation verifications to verify the compliance of importers as part of its day-to-day business.

A review of post-clearance valuation verifications conducted between 2016 and 2019, largely involving imports of apparel and footwear in line with CBSA’s verification priorities,footnote 8 concluded that nearly 10% of all compliance verifications involved the use of an earlier, lower-priced sale between two foreign entities resulting in a lower declared value for duty. Of this 10%, a large majority of the verifications (85%) were in respect of NRIs primarily located in the United States, with 10% involving Canadian subsidiaries and the remaining 5% involving Canadian companies without foreign ties. It is unclear how the Canadian companies without foreign ties had access to a previous lower-priced sale, but they are deemed to be less likely to successfully utilize the current regulatory gap. Given that NRIs represented the majority, the analysis was narrowed to verifications involving NRIs only. This analysis concluded that nearly 30% of all compliance verifications involving NRIs used an earlier, lower-priced sale between two foreign entities. Further, based on a sample, it was estimated that the declared value for duty was 44% lower on average.

Scenarios

Generally, there are two scenarios that involve the declaration of a lower VFD based on a sale between foreign entities, as opposed to the transaction value of the last sale for export to a buyer located in Canada:

- (1) An NRI imports the goods to fulfill an agreement to sell to a buyer located in Canada. When calculating the value of the goods, based on which duties and taxes are payable, an NRI uses its own purchase price of these goods for the purpose of calculating VFD, rather than using the price to the buyer located in Canada. For the NRI in this case, its own purchase price of the goods is lower than what the buyer located in Canada would have paid. Therefore, the NRI values the goods based on a lower price and, as a result, pays less in duty on these imported goods. The NRI is able to do so under the premise that the importation was made for stock inventory purposes even though the goods have already been contracted for sale.

- (2) A transaction between related parties, such as a parent company and a subsidiary, takes place and results in goods being imported directly to Canada from the manufacturer in a third country. In this case, the foreign parent company’s purchase price from the manufacturer is declared for the purposes of calculating VFD, rather than the Canadian subsidiary’s purchase price. As the purchase price from the manufacturer is lower than what the Canadian subsidiary would have paid, less duty is paid.

Declaring a lower value for duty by using an earlier (lower-priced) sale between foreign entities is possible in these scenarios for two reasons. First, these NRIs and Canadian subsidiaries have access to the transaction information for the earlier sale. Second, the above-referenced decisions from the CITT resulted in a narrow interpretation of “sold for export to Canada” and identified a loophole in the definition of “purchaser in Canada” that permits the use of a sale between two foreign entities in circumstances that were not foreseen when the amendments to the Regulations came into force in 1997.

Objective

The proposed regulatory amendments would

- ensure that Canadian importers that compete with NRIs are not at a disadvantage as a result of the current regulatory framework, which allows the latter to declare a lower purchase price when calculating VFD;

- provide a legal basis to ensure the government collects duties on the sale that brought the goods to Canada, thereby preventing revenue leakage stemming from NRIs ability to declare an earlier sale in the supply chain;

- ensure that Canada meets its obligations under the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement and to Canada’s trading partners regarding the methods of calculating VFD; and

- ensure that Canada fosters a fair and predictable environment for the trading community that is consistent with the objectives of free and liberalized trade and in compliance with the internationally agreed methods of calculating VFD.

In addition, these amendments would contribute to Canada’s domestic economic recovery priorities by minimizing the risk of foregone customs revenues, creating enforceable measures that generate revenue, removing any incentive for businesses to minimize their operations or presence in Canada, and removing disadvantages to Canadian businesses in a post-COVID-19 environment.

Description

Sold for export to Canada

Currently, the Customs Act and the Regulations do not outline a definition of “sold for export to Canada” and, because the current scope of eligibility of a “purchaser in Canada” has been interpreted broadly, regulatory amendments are required in order to uphold the “last sale rule”. Bill C-30, Budget Implementation Act, 2021, No. 1, which received royal assent on June 29, 2021, includes a legislative amendment to the Customs Act to allow the phrase “sold for export to Canada” to be defined by regulations (Part 4, Division 18, section 212). Specifically, this proposal would add a definition of “sold for export to Canada” to the Regulations to identify the relevant sale for export that forms the basis of the transaction value within the Customs Act that aligns with the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement.

The objectives of defining this term are the following:

- Ensure that the term “sale” is interpreted in a broad sense to include agreements, arrangements or any other type of understanding that cause goods to be exported to Canada;

- Ensure that, in a series of sales, the last sale to the buyer in the country of import (Canada), and not an earlier sale between two foreign entities, is to be used as a basis for determining VFD;

- Uncouple, going forward, the “sale for export” from the “transfer of title to the importer” as determined by the 2001 Supreme Court of Canada decision;

- Clarify that any form of intent to sell or purchase the goods is a sale for export to Canada, including agreements or any other arrangements to purchase that cause the goods to be imported to Canada; and

- Specify that if the goods are subject to more than one sale for export to Canada, the applicable transaction for VFD will be the last sale in the supply chain that brought the goods into Canada, irrespective of the chronological order of the sales.

Sales that occur in Canada and do not cause the goods to be exported to Canada will not be used in the determination of the VFD of imported goods.

Purchaser in Canada

In addition, the current definition of “purchaser in Canada” within the Regulations would be amended to remove linkages to the concepts of “resident” and “permanent establishment”. The purchaser would be the person who purchases or will purchase the goods in the relevant sale for export to Canada.

As a result of this change, and in order to align with amendments described above, the terms “permanent establishment” and “resident” would be repealed, as they would no longer be relevant to the objective of the Regulations.

These amendments would ensure that the VFD of imported goods, when determined according to the transaction value method, is based on the sale that causes the goods to be exported to Canada.

A series of sales scenarios: Relevant sale for export to a purchaser in Canada

In the context of the proposed regulatory amendments, the following examples illustrate the relevant sale for export to Canada (i.e. last sale, including any type of arrangement) for determining the transaction value under section 48 of the Customs Act, where the goods are subject to more than one sale or other type of arrangement prior to the importation of the goods into Canada. Information on who acts as the importer of record or who holds the title of the goods at the time of importation is not provided in these examples because this would not be relevant to the determination of the sale for export to Canada.

Scenario 1

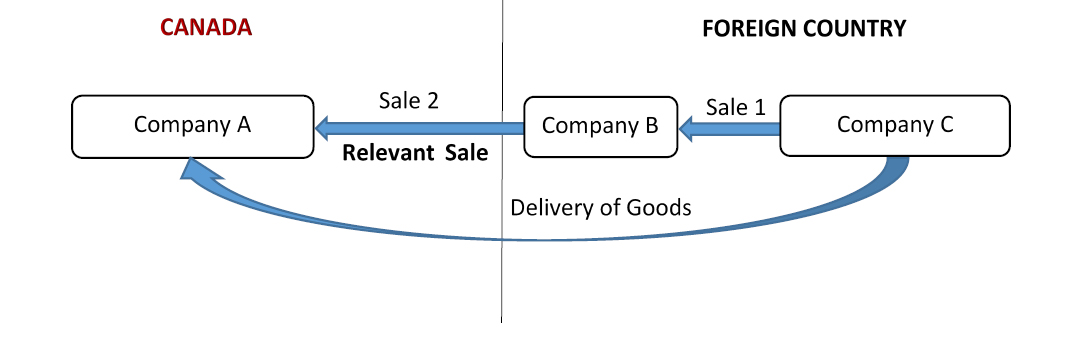

Figure 1: Visual representation of the first importation scenario

Figure 1: Visual representation of the first importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There are three companies identified in a row of horizontal boxes. Company A is shown in Canada and companies B and C, in the foreign country. There are two arrows pointing left between the three companies illustrating two sales, and a third arrow between company C and company A illustrating the delivery of the goods. A text box identifies the second sale between company B and company A as the relevant sale.

Company A, which is located in Canada, purchases goods from company B, located in a foreign country. Company B then contracts with company C, also located in the foreign country, to fill the order. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company C to company B, and (2) from company B to company A. The goods are shipped directly from company C to Canadian company A.

Both sales are considered to have occurred prior to importation. Sale 2 is the sale that causes the goods to be exported to Canada and is the last sale in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it would be considered the sale for export to Canada and used to determine the transaction value of the goods.

Scenario 2

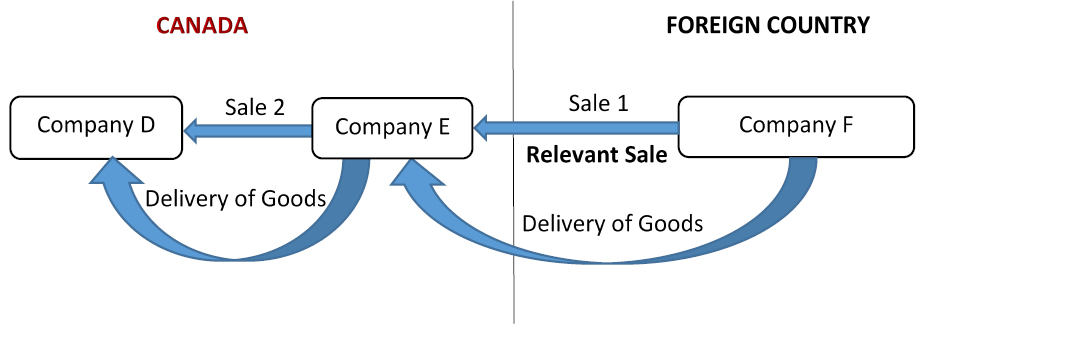

Figure 2: Visual representation of the second importation scenario

Figure 2: Visual representation of the second importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There are three companies identified in a row of horizontal boxes. Companies D and E are shown in Canada and company F, in the foreign country. There are two arrows pointing left between the three companies illustrating two sales, and two more arrows illustrating the delivery of the goods from company F to company E and then company E to company D. A text box identifies the first sale between company F and company E as the relevant sale.

Company E, which is located in Canada, purchases goods from company F, located in a foreign country. The goods are shipped to company E’s warehouse in Canada. Following the importation of the goods, company E sells the goods to company D in Canada, with no prior agreement. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company F to company E, and (2) from company E to company D.

The only sale that is considered to have occurred prior to the importation of the goods into Canada is sale 1, from company F to company E. It is this sale that causes the goods to be exported to Canada. Therefore, sale 1 would be the sale for export to Canada that would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 3

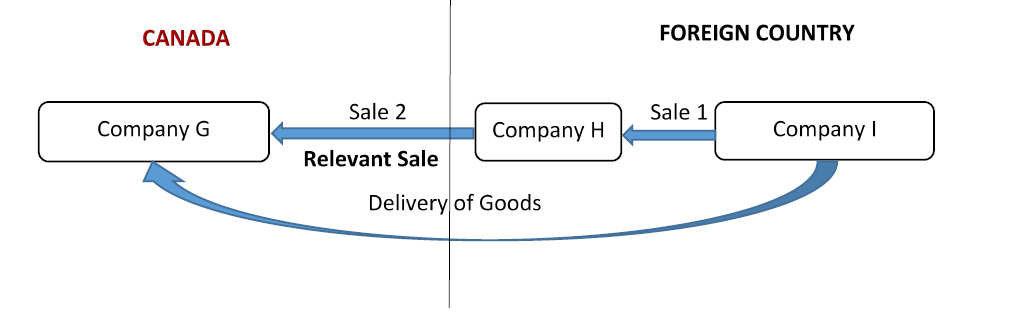

Figure 3: Visual representation of the third importation scenario

Figure 3: Visual representation of the third importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There are three companies identified in a row of horizontal boxes. Company G is shown in Canada and companies H and I, in the foreign country. There are two arrows pointing left between the three companies illustrating two sales, and a third arrow illustrating the delivery of the goods from company I to company G. A text box identifies the second sale between company H and company G as the relevant sale.

Company G, which is located in Canada, enters into an agreement to purchase goods from company H, located in a foreign country. Company H then contracts with company I, also located in the foreign country, to fill the order. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company I to company H, and (2) the agreement to sell between company H and company G. The goods are shipped directly from company I to company G in Canada.

Both sale 1 and the agreement to sell (sale 2) are considered to have occurred prior to importation. The agreement between company H and company G, which is considered a sale for export to Canada, causes the goods to be exported to Canada and provides for the last transfer of the goods in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it would be sale 2, the agreement between company H and company G, that would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 4

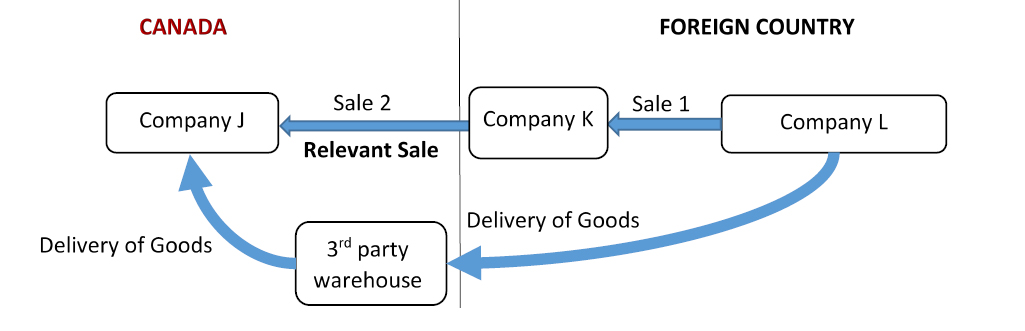

Figure 4: Visual representation of the fourth importation scenario

Figure 4: Visual representation of the fourth importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There are three companies identified in a row of horizontal boxes. Company J is shown in Canada and companies K and L, in the foreign country. There is an additional box under company J identifying a third-party warehouse in Canada. There are two arrows pointing left between the three companies illustrating two sales, and two more arrows illustrating the delivery of the goods from company L to the warehouse and then from the warehouse to company J. A text box identifies the second sale between company K and company J as the relevant sale.

Company J, which is located in Canada, places a blanket purchase order for goods with company K, located in a foreign country. Company K then places an order for the goods with company L, also located in the foreign country. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company L to company K, and (2) the agreement (blanket purchase order) between company K and company J. The goods are first shipped to a third-party warehouse, located in Canada, and then to company J.

Both sale 1 and the blanket purchase order (sale 2) are considered to have occurred prior to importation. The agreement between company K and company J, which is considered a sale for export to Canada, causes the goods to be exported to Canada and provides for the last transfer of the goods in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it would be sale 2, the agreement between company K and company J, that would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 5

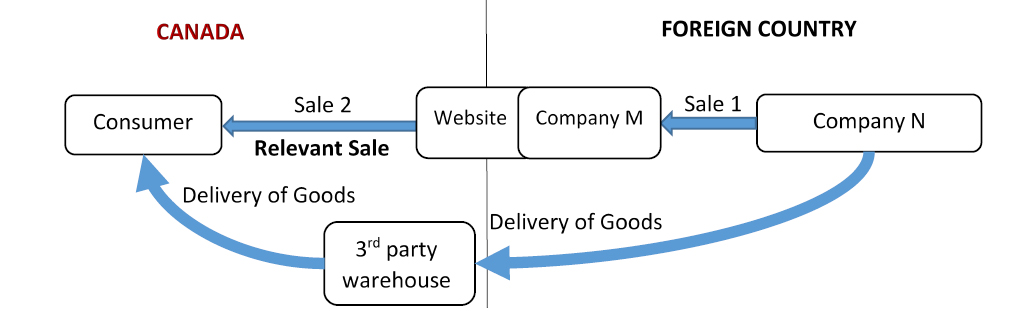

Figure 5: Visual representation of the fifth importation scenario

Figure 5: Visual representation of the fifth importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There is a row of three horizontal boxes. The first box on the left shows the consumer is located in Canada. The second box illustrates that company M is located in a foreign country and has a website. The final box on the right shows company N in the foreign country. There is an additional box identifying a third-party warehouse in Canada. There are two arrows pointing left between the three horizontal boxes illustrating two sales, and two more arrows illustrating the delivery of the goods from company N to the warehouse and then from the warehouse to the consumer. A text box identifies the second sale between company M and the consumer as the relevant sale.

A consumer in Canada places an order online through company M’s website and pays for the goods. Company M, located in a foreign country, then places an order with company N, also located in the foreign country, to fill the order. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company N to company M, and (2) from company M to the consumer. The goods are shipped by company N, through a third-party warehouse located in Canada, to the consumer in Canada.

Both sales are considered to have occurred prior to importation. Sale 2, from company M to the Canadian consumer, is the sale that causes the goods to be exported to Canada and is the last sale in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, sale 2, from company M to the consumer, would be considered the sale for export to Canada and would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 6

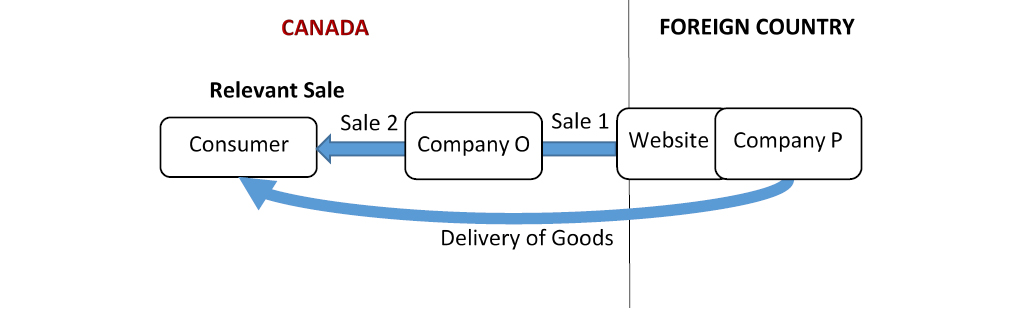

Figure 6: Visual representation of the sixth importation scenario

Figure 6: Visual representation of the sixth importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There is a row of three horizontal boxes. The first box on the left shows thea consumer is located in Canada. The second box illustrates that company O is located in Canada. The final box on the right shows that company P is located in the foreign country and has a website. There are two arrows pointing left between the three horizontal boxes illustrating two sales, and a third arrow illustrating the delivery of the goods from company P to the consumer. A text box identifies the second sale to the consumer as the relevant sale.

A consumer in Canada places an order online and pays for goods through the website of company P, which is located in a foreign country. The website through which the order is placed is set up to represent company P’s related company O, a Canadian entity, to sell goods in Canada. The order placed through the website automatically generates two invoices at the same time: one from company P to its related company, company O, and another from company O to the consumer. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company P to company O, and (2) from company P, through company O, to the consumer. Company P fills the order and ships the goods directly to the consumer. Company O pays company P for the goods and also pays company P a fee for online services.

Both sales are considered to have occurred prior to importation. The order from the consumer sets off the chain of events that cause the goods to be exported to Canada and is the last sale in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it is sale 2 from company P, through company O, to the consumer that would be considered the sale for export to Canada and it is the price to the Canadian consumer that would be used as the basis to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 7

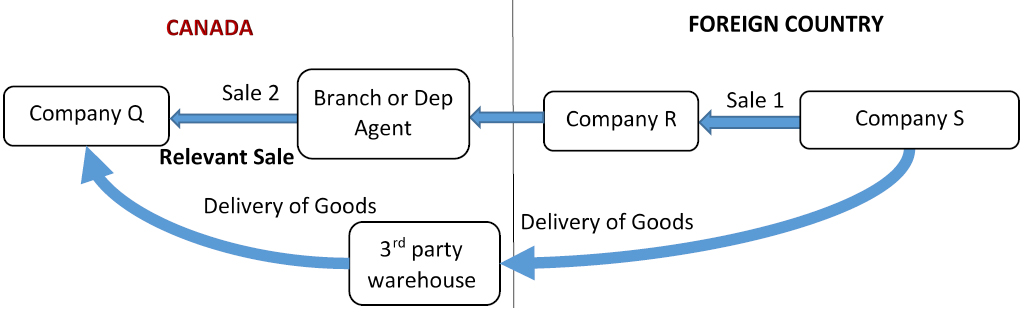

Figure 7: Visual representation of the seventh importation scenario

Figure 7: Visual representation of the seventh importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There is a row of four horizontal boxes. The first box on the left shows company Q is located in Canada. There is a second box in Canada showing a branch or dependent agent. The remaining two boxes show companies R and S are located in a foreign country. There is an additional box identifying a third-party warehouse in Canada. There are three arrows pointing left between the four horizontal boxes illustrating a sale between company S and company R, a transfer between company R and its branch or dependent agent, and a sale to company Q. Two more arrows illustrate the delivery of the goods from company S to the warehouse and then from the warehouse to company Q. A text box identifies the second sale to company Q as the relevant sale.

Company Q, located in Canada, places an order with a company in a foreign country, company R, through its branch or dependent sales agent located in Canada. Company R contracts with another company in the foreign country, company S, to fill the order. The goods are the subject of two sales: (1) from company S to company R, and (2) from company R, through its branch or dependent agent, to company Q. The goods are shipped from company S to company Q through a third-party warehouse in Canada.

The intercompany transfer from company R to its Canadian branch cannot be a sale, as the branch is not a separate legal entity. Likewise, in the case of a dependent sales agent, although a separate legal entity, it does not purchase the goods. Both the sale between Company S and Company R and the sale between Company R and Company Q are considered to have occurred prior to importation. The sale from company R, through its branch or dependent agent, to company Q is the sale that causes the goods to be exported to Canada and is the last sale in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it would be considered the sale for export to Canada and would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Scenario 8

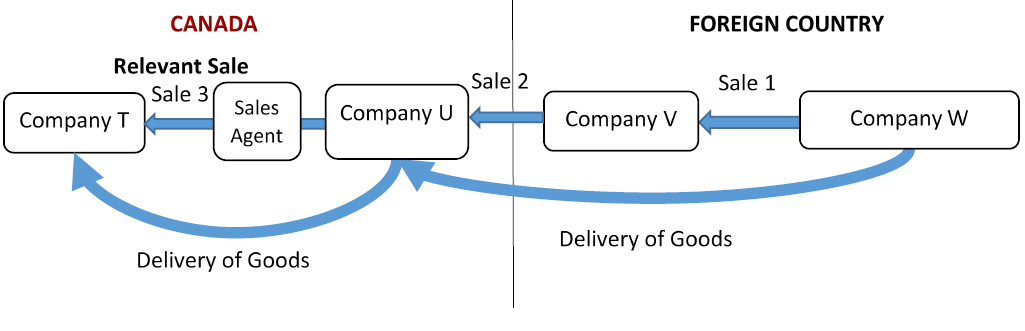

Figure 8: Visual representation of the eighth importation scenario

Figure 8: Visual representation of the eighth importation scenario - Text version

There is a line down the middle of the diagram representing a border separating Canada on the left and a “foreign country” on the right. There is a row of five horizontal boxes. The first box on the left shows company T is located in Canada. The next two boxes in Canada identify a sales agent and company U. The remaining two boxes show companies V and W are located in a foreign country. There are three arrows pointing left illustrating a sale between company W and company V, a sale between company V and company U, and a sale between company U, through its sales agent, to company T. Two more arrows illustrate the delivery of the goods from company W to company U and then from company U to company T. A text box identifies the third sale to company T as the relevant sale.

Company U, located in Canada, is a wholly owned subsidiary of company V, which is located in a foreign country. Sales in Canada are solicited using sales agents.

In this case, the sales agent has obtained an order from company T, located in Canada, and the order is placed through company V’s computer system. Once the purchase order is accepted by company V, two invoices are automatically generated: one from company U to company T and another from company V to company U. Company V then contracts with company W, also located in the foreign country, to fill the order. The goods are the subject of three sales: (1) from company W to company V, (2) from company V to company U (intercompany sale) and (3) from company U to company T. The goods are shipped from company W to company T, through company U.

All sales are considered to have occurred prior to importation. The order from company T, sets off the chain of events that cause the goods to be exported to Canada and provides for the last transfer of the goods in the supply of the goods to Canada. Therefore, it is sale 3, from company U to company T, on the authority of company V, that would be considered the sale for export to Canada and would be used to determine the transaction value of the imported goods.

Regulatory development

Consultation

Between June 4 and July 4, 2021, the CBSA conducted a preliminary consultation on these regulatory amendments, allowing all Canadians, including key industry stakeholders, the opportunity to ask questions or provide feedback. The implicated stakeholders were notified about this consultation via email correspondence from CBSA.

In general, the received feedback highlighted concerns ranging from potential job losses to violations of trade agreements, as well as uncertainty whether the amendments would be retroactive in nature. These comments served to highlight their inability to provide meaningful feedback without seeing draft regulatory text, and, therefore, reinforced their desire for the proposed regulatory amendments to be prepublished in the Canada Gazette, Part I (CGI), for further review and comment. These amendments will not be retroactive in nature, and through this prepublication, stakeholders will have the opportunity to provide written comments on the specific language of the proposed regulatory amendments.

A common element identified through feedback from stakeholders was the recommendation that the overall revenue impact to the Government of Canada be considered, including the loss of potential income taxes and potential job losses associated with the closing of this regulatory gap. The CBSA views these impacts to be out of scope and not related to the intended purpose of collecting customs duties. Therefore, it would be neither feasible nor reasonable to estimate lost income taxes that were only incurred due to a loophole that incentivized NRIs and Canadian subsidiaries to create a minimum presence in Canada, and pay income taxes as a result, to meet the permanent establishment threshold.

Stakeholders also noted that the new $150 de minimis footnote 9 provision within the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA)footnote 10 would potentially encourage NRIs to relocate in favour of shipping from the U.S. or Mexico to take advantage of this rule in the e-commerce environment. While it is true that Canada is facilitating e-commerce by enabling de minimis and NRIs may restructure to take advantage, the CBSA non-compliance review reveals that 93% of the would-be affected NRIs are located in the United States and can already avail themselves of de minimis changes and may pull their Canadian presence irrespective of these regulatory amendments.

Concerns were also raised that the proposed changes would be inconsistent with the approach of Canada’s largest trading partners. With the exception of the United States, Canada is not aware of any other World Trade Organization members that do not apply the last sale rule in instances where a series of sales occur before importation of goods. While the United States allows the use of “the first or earlier sale” as the basis for calculating the customs value of imported goods, its use is minimal, as the importer must demonstrate with documentary evidence that the first sale is a sale for exportation to the United States and the importer must meet all other customs requirements (e.g. demonstrate that the price between related foreign entities is not influenced by their relationship).footnote 11 This proposal intends to bring Canada into alignment with international consensus set by the World Customs Organization under the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement.

Finally, the responding stakeholders highlighted that these proposed changes were inconsistent with generally accepted accounting principles and sound business practices. The CBSA acknowledges that businesses have modernized and adapted much quicker than the Government of Canada could adapt its laws and regulations to the evolving landscape of e-commerce, allowing NRIs to adapt and benefit from the outdated legislative and regulatory framework in order to gain competitive advantage. However, it must also be noted that these businesses have been aware that the CITT’s decisions were contrary to CBSA administrative practice and interpretation of the Transaction Value Method within the Customs Act, and that informal consultations on these proposed changes have been ongoing since 2010.

Modern treaty obligations and Indigenous engagement and consultation

As required by the Cabinet Directive on the Federal Approach to Modern Treaty Implementation, an assessment of modern treaty implications was conducted. The assessment examined the geographical scope and subject matter of the initiative in relation to modern treaties in effect and did not identify any potential modern treaty impacts or obligations. The CBSA would continue to assess potential impacts as new modern treaties are implemented.

Instrument choice

Status quo

The primary risk associated with not proceeding with these regulatory amendments is that the CBSA would continue to be unable to enforce the relevant provisions of the Customs Act. Failing to align Canadian law with the CBSA’s longstanding VFD policy and international consensus would only encourage importers to seek avenues to declare a lower VFD on goods that they import and could increase the number of VFD disputes. Ultimately, status quo would continue to disadvantage Canadian companies and would result in the continued risk of significant foregone customs revenues for the Government of Canada.

Policy change

An option was considered for the CBSA to amend its policies to reflect Canadian law and apply the outcomes of the CITT decisions to all importers (not just those who request it) in order to achieve greater consistency with the outcomes of jurisprudence and reduce the possibility of appeals. By relying solely on Canadian law as it is currently written and amending policies to align with case law, Canada would not only violate its obligations under the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement, it could encourage multinational corporations and other importers to minimize their operations, presence and/or investments in Canada and to structure their sales or trade chains in such a fashion as to lower their declared VFD. This option would also further disadvantage Canadian importers and compound lost customs revenues for the Government of Canada.

Regulatory amendments

Since the loophole that incentivizes NRIs and Canadian subsidiaries to create a minimum presence in Canada is in the Regulations, the only way to close that loophole is through regulatory amendments. In addition to creating a level playing field for Canadian importers and NRIs, this option would align Canada with the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement. This proposal was also endorsed by the Department of Finance Canada, as evidenced by that department’s support of the proposed VFD amendment to the Customs Act that was included in Bill C-30, Budget Implementation Act, 2021. Regulatory amendments are also necessary to give effect to the amendment to the Customs Act.

Regulatory analysis

Benefits and costs

Baseline and regulatory scenarios

Baseline scenario

To understand the impact of the proposed regulatory change, it is necessary to outline the baseline and the regulatory scenario. In the baseline scenario, the ability of NRIs and Canadian subsidiaries to declare a lower value on goods imported into Canada is unchanged — they continue to use an earlier sale price and not the sale that would bring the goods into Canada, as intended by the Customs Valuation Agreement. This continues to place domestic importers at a distinct disadvantage, as they do not have access to transaction information for earlier sales, and cannot use loopholes created by CITT decisions that have narrowly interpreted the “sold for export to Canada” definition. This places domestic importers at a distinct disadvantage, as they are unable to reduce the amount of any duties payable by declaring the lower transaction value from a preceding sale, instead of the sale that actually brought the goods to Canada. Keeping the baseline scenario only favours NRIs and Canadian subsidiaries, as they would continue to be able to declare the value for duty from an earlier, lower-priced sale, resulting in significantly less duty paid on the exact same goods imported by domestic importers.

Regulatory scenario

Under the regulatory scenario, NRI duties are calculated using the sale that brought the goods to Canada.

The proposed amendments would help address the competitive imbalance between Canadian importers and other importers and establish a consistent and reliable method for calculating the value for duty for all importers.

While compliance verifications were limited during 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, a review of the data on VFD based on the Transaction Value Method revealed a significant growth of NRIs’ share (14%) of the total VFD declared to the CBSA. Therefore, it is reasonable to expect that NRIs share of total VFD would continue to rise with the growth of e-commerce.

Benefits

The regulatory proposal would result in significant revenue increases for the Government of Canada. Over the next 10 years, the Government of Canada would see increased revenues starting with $181.8 million in duties in 2023, rising to 273.2 million by 2031, an average of $224.7 million per year in nominal terms.

Since the regulatory amendments are intended to give clearer and enforceable direction to importers when determining which sale price is to be used for assessing the value of their imports, it is anticipated that local importers would now compete on a level playing field with NRIs and reduce potential revenue losses to the Government of Canada, while ensuring the Regulations impose no further cost on local importers.

Costs

The CBSA would incur minor costs related to implementation, communication and outreach activities needed as a result of the regulatory amendments (e.g. updating departmental memoranda and work instruments, as well as responding to functional guidance requests and updating web content on the CBSA webpage). No incremental staff will need to be hired. The proposed regulations are not expected to result in increased compliance, enforcement, and verification costs to CBSA. Post-importation verifications of VFD are currently conducted, and would continue to be conducted as part of broader compliance verification activities.

With NRIs accounting for about 11% of the total VFD declared to the CBSA under the transaction value method (using data from 2016 to 2019), it is not anticipated that these firms would be able to significantly raise prices on goods without negatively impacting sales and lowering market share. As a result, higher prices for Canadians on goods imported by NRI firms are expected to be minimal. Instead, the NRIs are likely to absorb the additional duties as a cost of doing business and are unlikely to pass them on to Canadian consumers.

Notwithstanding that NRIs would incur higher duty costs resulting from the regulatory amendments in this proposal, these costs are not accounted for in this cost benefit analysis as per the Cabinet Directive on Regulation,footnote 12 as they are not Canadian companies. It is important to note that Canadian subsidiaries, considered Canadian companies, represented approximately 10% of the verifications that used an earlier, lower priced sale resulting in a lower declared value for duty; however, they were not included in the analysis, as these additional duties were determined to be out of scope since they would be treated as taxes.

It is estimated that, had goods imported by NRIs been declared using the VFD from the sale that brought the goods to Canada, NRIs would have declared an average of $14.7 billion more from 2016–19, with estimated additional duties payable of $150 million annually for NRIs.

Small business lens

Analysis under the small business lens concluded that the proposed Regulations would not impact Canadian small businesses.

One-for-one rule

The one-for-one rule does not apply as there is no incremental change in the administrative burden on business and no regulatory titles are repealed or introduced.

Regulatory cooperation and alignment

Canada

The proposed amendments would provide both importers and the CBSA with the tools needed to determine the VFD in a manner consistent with Canada’s obligations under the World Trade Organization’s Customs Valuation Agreement (using the Transaction Value Method). This approach is also aligned with international consensus set by the World Customs Organization on “the last sale rule” (i.e. the last sale into the country of importation).

United States

As a World Trade Organization member, the United States is also bound by the Customs Valuation Agreement, which sets the Transaction Value Method as the primary method for valuing imported goods. The United States government sought to regulate the “last sale rule,” which would align with international consensus; however, the proposal for regulatory change was withdrawn due to objections from the trading community and a report on the minimal use of the first sale by the International Trade Commission.

European Union

As a World Trade Organization member, the European Union (EU) is also bound by the Customs Valuation Agreement, which sets the Transaction Value Method as the primary method for valuing imported goods. In 2016, European Union legislation was amended to provide that the “last sale” could be the only basis for customs valuation in a series of sales scenario.footnote 13

Other World Trade Organization members

Other than the United States, Canada is not aware of any World Trade Organization members that do not apply the “last sale rule” in instances where a series of sales occur before importation.

Strategic environmental assessment

In accordance with the Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals, a preliminary scan concluded that a strategic environmental assessment is not required.

Gender-based analysis plus

A preliminary gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) analysis was completed and it was determined that these Regulations are not expected to have any gender-specific impacts.

Implementation, compliance and enforcement, and service standards

Implementation

The regulatory amendments would come into force on the day on which section 212 of the Budget Implementation Act, 2021, No. 1, chapter 23 of the Statutes of Canada, 2021, comes into force. If these regulatory amendments are registered after that day, they would come into force upon registration.

As part of the implementation plan for the proposed regulatory amendments, the CBSA would aim to conduct communication and outreach activities in order to inform internal and external stakeholders on the changes. These activities would include, but would not be limited to, updating relevant departmental memoranda and other work instruments, as well as updating web content on the CBSA web page and publishing updates via social media. The CBSA plans to further refine the outreach strategy closer to the coming-into-force date.

Compliance and enforcement

Enforcement and compliance verification strategies would not change with the regulatory amendments.

The CBSA relies primarily on voluntary compliance for the assessment of duties and conducts post-importation verifications of importers to confirm the compliance of importers as part of its day-to-day business. The proposed amendments are intended to give clearer direction to importers when determining which sale price is to be used for assessing the value of their imports.

The CBSA continues to deliver on its mandate by focusing efforts on trade compliance to enhance customs revenue generation under the strengthening border compliance strategic objective of the 2019–2020 Departmental Plan. It was also identified in the CBSA’s previous departmental plan that, in order to enforce trade compliance and ensure the collection of appropriate customs revenues, the CBSA would need to modernize the related legislative and regulatory frameworks. The regulatory amendments in this proposal and its related legislated amendments would support CBSA priorities by strengthening Canada’s customs system to ensure compliance with the internationally agreed methods of calculating VFD.

Contact

Valerie Dinis

Acting Director

Commercial and Trade Policy Division

Traveller, Commercial, and Trade Policy Directorate

Strategic Policy Branch

Canada Border Services Agency

Email: CBSA.OCT/CECO.ASFC@cbsa-asfc.gc.ca

PROPOSED REGULATORY TEXT

Notice is given that the Governor in Council, under paragraph 164(1)footnote a of the Customs Act footnote b, proposes to make the annexed Regulations Amending the Valuation for Duty Regulations.

Interested persons may make representations concerning the proposed Regulations within 30 days after the date of publication of this notice. They are strongly encouraged to use the online commenting feature that is available on the Canada Gazette website but if they use email, mail or any other means, the representations should cite the Canada Gazette, Part I, and the date of publication of this notice, and be sent to Valerie Dinis, Acting Director, Commercial and Trade Policy Division, Traveller, Commercial, and Trade Policy Directorate, Strategic Policy Branch, Canada Border Services Agency, 100 Metcalfe Street, 10th Floor, Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0L8 (email: CBSA.OCT/CECO.ASFC@cbsa-asfc.gc.ca).

Ottawa, May 18, 2023

Wendy Nixon

Assistant Clerk of the Privy Council

Regulations Amending the Valuation for Duty Regulations

Amendments

1 The long title of the Valuation for Duty Regulations footnote 14 is replaced by the following:

Valuation for Duty Regulations

2 Section 1 of the Regulations and the heading before it are repealed.

3 The heading before section 2 and sections 2 and 2.1 of the Regulations are replaced by the following:

Definition

2 In these Regulations, Act means the Customs Act.

Definitions for the Purposes of Subsection 45(1) of the Act

2.01 (1) For the purposes of subsection 45(1) of the Act, sold for export to Canada means, in respect of goods, to be subject to an agreement, understanding or any other type of arrangement — regardless of its form — to be transferred, in exchange for payment, for the purpose of being exported to Canada, regardless of whether the transfer of ownership of the goods is completed before or after the goods are imported.

(2) If the goods are subject to two or more agreements, understandings or other types of arrangement described in subsection (1), the applicable agreement, understanding or arrangement for the purposes of that subsection is the one respecting the last transfer of the goods in the supply chain among the transfers under those agreements, understandings or arrangements, regardless of the order in which the agreements, understandings or arrangements were entered into.

2.1 For the purposes of subsection 45(1) of the Act, purchaser in Canada means, in respect of goods that are the subject of an agreement, understanding or any other type of arrangement referred to in section 2.01, the person who, under that agreement, understanding or arrangement, purchases or will purchase the goods, regardless of whether the person is the importer of the goods or when the person makes payments in respect of the goods.

Coming into Force

4 These Regulations come into force on the day on which section 212 of the Budget Implementation Act, 2021, No. 1, chapter 23 of the Statutes of Canada, 2021, comes into force, but if they are registered after that day, they come into force on the day on which they are registered.

Terms of use and Privacy notice

Terms of use

It is your responsibility to ensure that the comments you provide do not:

- contain personal information

- contain protected or classified information of the Government of Canada

- express or incite discrimination on the basis of race, sex, religion, sexual orientation or against any other group protected under the Canadian Human Rights Act or the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms

- contain hateful, defamatory, or obscene language

- contain threatening, violent, intimidating or harassing language

- contain language contrary to any federal, provincial or territorial laws of Canada

- constitute impersonation, advertising or spam

- encourage or incite any criminal activity

- contain external links

- contain a language other than English or French

- otherwise violate this notice

The federal institution managing the proposed regulatory change retains the right to review and remove personal information, hate speech, or other information deemed inappropriate for public posting as listed above.

Confidential Business Information should only be posted in the specific Confidential Business Information text box. In general, Confidential Business Information includes information that (i) is not publicly available, (ii) is treated in a confidential manner by the person to whose business the information relates, and (iii) has actual or potential economic value to the person or their competitors because it is not publicly available and whose disclosure would result in financial loss to the person or a material gain to their competitors. Comments that you provide in the Confidential Business Information section that satisfy this description will not be made publicly available. The federal institution managing the proposed regulatory change retains the right to post the comment publicly if it is not deemed to be Confidential Business Information.

Your comments will be posted on the Canada Gazette website for public review. However, you have the right to submit your comments anonymously. If you choose to remain anonymous, your comments will be made public and attributed to an anonymous individual. No other information about you will be made publicly available.

Comments will remain posted on the Canada Gazette website for at least 10 years.

Please note that public email is not secure, if the attachment you wish to send contains sensitive information, please contact the departmental email to discuss ways in which you can transmit sensitive information.

Privacy notice

The information you provide is collected under the authority of the Financial Administration Act, the Department of Public Works and Government Services Act, the Canada–United States–Mexico Agreement Implementation Act,and applicable regulators’ enabling statutes for the purpose of collecting comments related to the proposed regulatory changes. Your comments and documents are collected for the purpose of increasing transparency in the regulatory process and making Government more accessible to Canadians.

Personal information submitted is collected, used, disclosed, retained, and protected from unauthorized persons and/or agencies pursuant to the provisions of the Privacy Act and the Privacy Regulations. Individual names that are submitted will not be posted online but will be kept for contact if needed. The names of organizations that submit comments will be posted online.

Submitted information, including personal information, will be accessible to Public Services and Procurement Canada, who is responsible for the Canada Gazette webpage, and the federal institution managing the proposed regulatory change.

You have the right of access to and correction of your personal information. To seek access or correction of your personal information, contact the Access to Information and Privacy (ATIP) Office of the federal institution managing the proposed regulatory change.

You have the right to file a complaint to the Privacy Commission of Canada regarding any federal institution’s handling of your personal information.

The personal information provided is included in Personal Information Bank PSU 938 Outreach Activities. Individuals requesting access to their personal information under the Privacy Act should submit their request to the appropriate regulator with sufficient information for that federal institution to retrieve their personal information. For individuals who choose to submit comments anonymously, requests for their information may not be reasonably retrievable by the government institution.